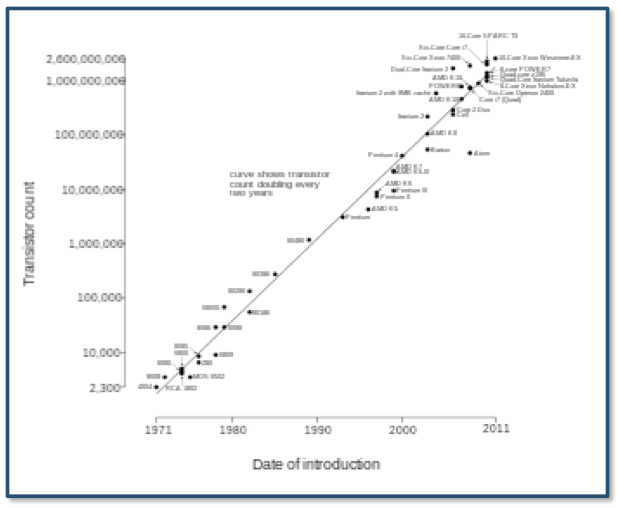

Moore’s Law—the principle of exponentially increasing processor speed—is a law of accretion. Progress is measured not in the smallness of the bit, but in the largeness of the processing power, the volume of computations per second.

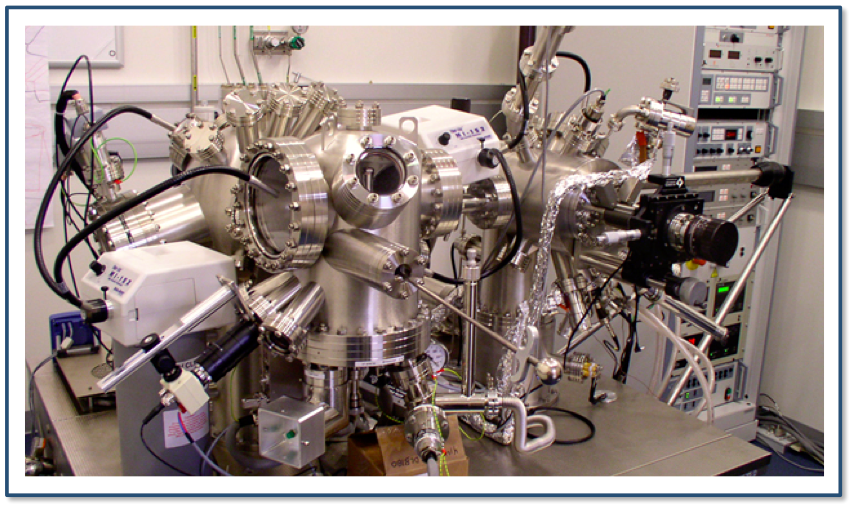

A single-atom bit would realize, perhaps, ultimate speed—and the end to Moore’s Law. To achieve such a feat of smallness, it will no doubt take a huge company like IBM, with a gigantic budget, big brains and steam-punkish rooms full of hardware like the scanning, tunneling microscope, below.

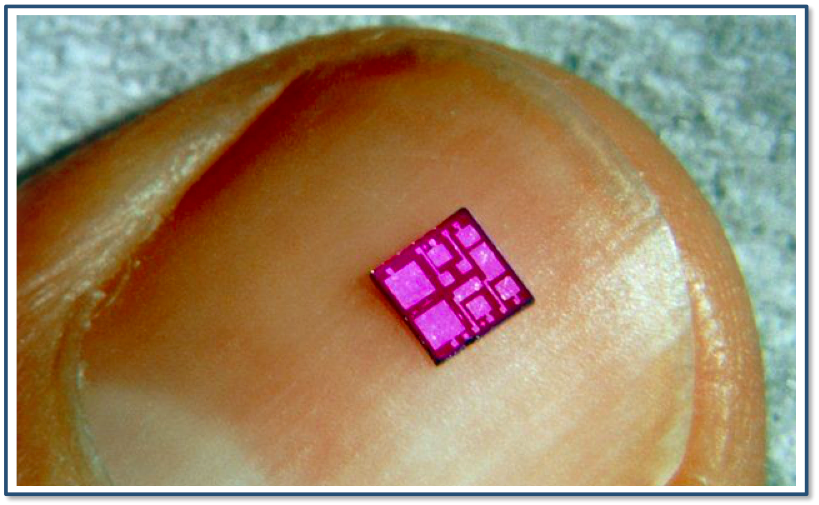

The quest for the atomic bit drives ambition and innovation. But we don’t seek the infinitesimal bit for its own sake. The smallness of it is only a means by which we achieve ultimate speed and power.

Computer engineering evokes an awe of the small made large. The drive of the discipline requires the packing of ever more information into smaller spaces. For decades we have marveled at its galloping feats of the miniscule.

The corollary to Moore’s Law is reduction, yet reduction chases the Law of More. Libraries disappear into thumb drives. More. We fight wars on a laptop. More. We slip the Internet into our pocket.

//On Smallness_2//