When I first started “writing for the web ecology,” I asked whether writing could survive on the Internet. The question presupposed a sort of battle between the weakling word on one side, and the brute image on the other. But the question—and the dichotomy—was misplaced.

Words and images aren’t enemies, as might be supposed. Rather, both are cohorts in whatever good or mischief they are put to. They can pull in the same direction to devastating effect (see, e.g., 1024/13).

My kids are huge fans of the meme—those easy-to-chew visual candies that you can pop down on the bus or on the crapper. Most are stupid, some are brilliant. One of my favorites:

To be generous, you could say that the meme phenomenon is like an extended experiment in word-image orientation. They tell us a lot about how words and images work together.

Example 1:

a. The image arrests; it throws the punch:

b. Words change the image’s meaning; they redirect its force:

But it can work the other way around too.

Example 2:

a. Sometimes the image is dull and flat:

b. And words bring the party:

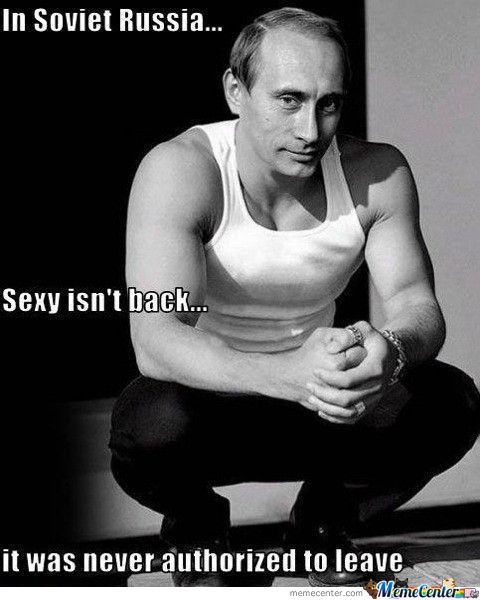

There’s just no easy way to disentangle word and image, except to admit that words require an interpretive skill—reading—whereas the image can simply be “seen.” But that doesn’t say everything. Reading images requires cultural knowledge. How else would this be so funny?

No, it doesn’t work to set the image up as the fall guy for the ills of the world, any more than does it work to complain about the inadequacies of words. Better to consider the uses they are put to, and complain (if it makes you feel better) about their content, about the cultural of distraction that has blossomed out of the fertile soil of the Internet.