Budapest, Hungary. February, 2016.

Home > Category Archives: Uncategorized

It’s hard to stop in the middle of the street and look up at the lights without feeling a little stupid. Try it.

Taken in the middle of Herrengasse, Vienna on November 19, 2015 at 10:03 pm CET. Cropped and edited with iPhoto.

The phone says I took this photo in Cleveland Park. Here is Henry behind the Washington Ballet while we wait for his sister Claire. He asked to go outside. Later, I found him coiled in a seat staring worriedly at something. I don’t know what he was looking at. I’ve learned not to spoil these things with questions.

Cropped to square and filtered with ‘Instant’ on iPhone.

An arrow slot of a stone tower. Taken in Bratislava, Slovakia, September 2015, using the iPhone pano feature. By gently rocking the phone back and forth while panning, you can get pano to produce these undulations.

Here’s the same effect, this time with a carved relief of the Last Supper in St. Martin’s cathedral. The undulations of pano give the scene the liquid feel of an El Greco. This version seems to me to be more uneasy, more expressive than the original.

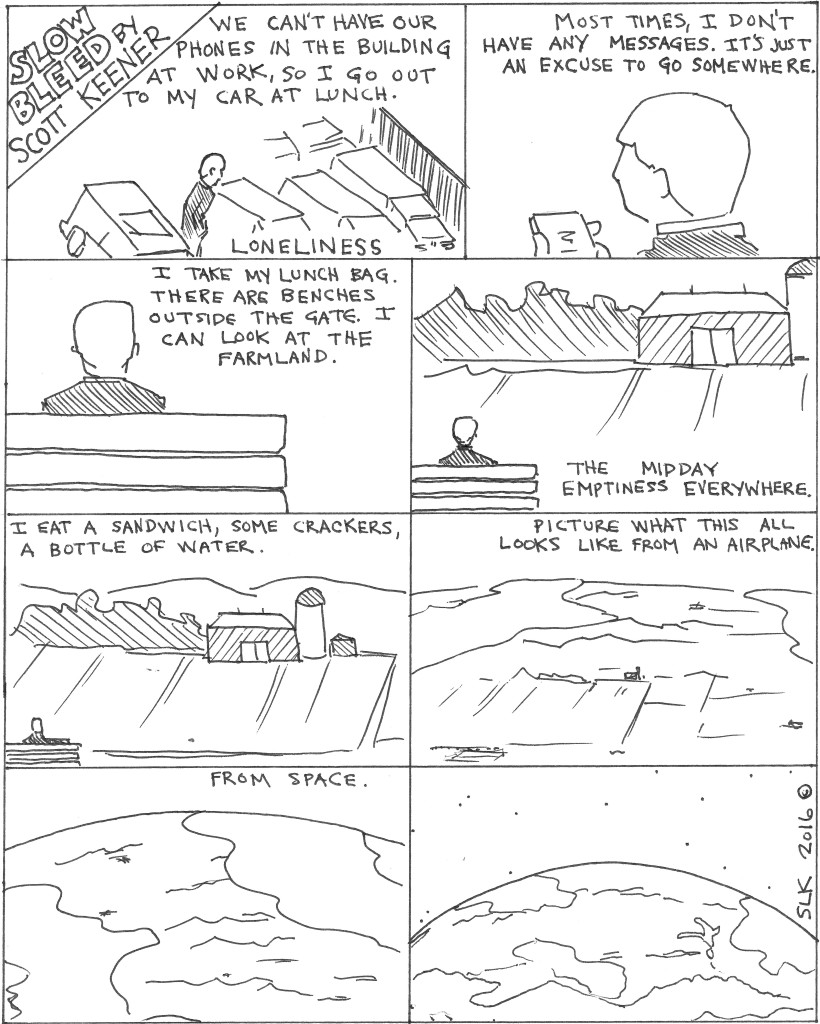

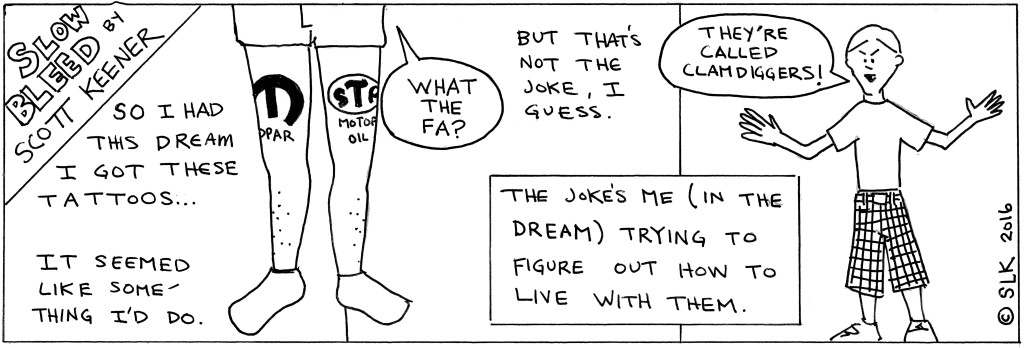

My daughter doesn’t like this website. Complains, “I don’t know what it means.” Her critique doesn’t come from a lack of smarts; she’s a savvier ten-year-old than I ever was.

It comes, I think, from not being able to place the website—from not being able to hear in it some ring of attitude and message. Yes, of course. That’s right.

Maybe I have sacrificed, preferring a kind of ambient bleed to the language of universality. But everything I put down here has a particular, if not constant, meaning to me. That is one essential criteria to my self-editing.

Of course, positions are important, and for that there are other, better fora. In this place, I’ve carved out a small hollow on the Interwebs as a kind of catch basin of the particular—the moving surface of an experience, transmitted in a language that is parcel to it.

There is discipline in smallness, consistently applied. Smallness, thus construed, is that which contains nothing more than the internal coherence of what is said or made or done now. It gathers what power it can from claiming to be nothing else.

//On Smallness/6//

This is the famed pale blue dot—the pixel seen from space when Voyager turned one last baleful glance toward home before slipping into the cold purgatory of drifting beyond.

Lay in the Carl Sagan voice-over, the Cosmos soundtrack. These sounds, like Catholic hymns or cicada dusk in Pennsylvania, were integral to the shaping of my wandering, self-flagellating, sometimes awestruck, always agnostic mind.

Voyager was built to drift forever, to seek, but to never find. In Star Trek, she is saved by a higher power. An alien race equips the probe with the means to know everything, to swallow worlds in the gullet of her imagination.

Me, a human, burdened either by my reptile brain or the stain of sin, I am left to listen to Pachelbel or Vangelis and experience the tingling simulacrum of insight—that expansive feeling of revelation full fire but lacking, painfully, in details.

This is metaphor of smallness.

Standing on Earth’s edge, I see in the black waters of night the light of a billion worlds. I know enough of science and circumstance to understand I will never reach them. And what remains of my religion are prayers against this darkness.

//On Smallness/5//

One sodden port call in Faliraki years ago, I put my finger on top of a piece of exposed rebar. “This is the most important thing in the universe!”

Pugs, my buddy, said this was stupid. And it was—a bunch of bleary nonsense.

But then again, part of me meant it. Brain full of wine, my attention had collapsed in layers until, through the periscope of inebriation, I could make out only one thing at a time.

And there was this rusty length of reinforcement bar, sticking out of the hotel roof.

Why was it there? Did this rebar, like those houses in Palestine, presage upper floors built for future generations? Or was it slipshod construction—a needless hazard waiting to maim a child?

Or did the importance of it come from being part of the great ever-moving? Like the blades of grass upon which angels blow, or the sparrows counted by their heavenly father, was this bit of rebar a logged coordinate in God’s counted universe?

Or, more improbably yet, could this rebar matter without any explanation at all, without the actuaries of heaven, or even the brief plaudits of a drunken sailor?

//On Smallness_4//

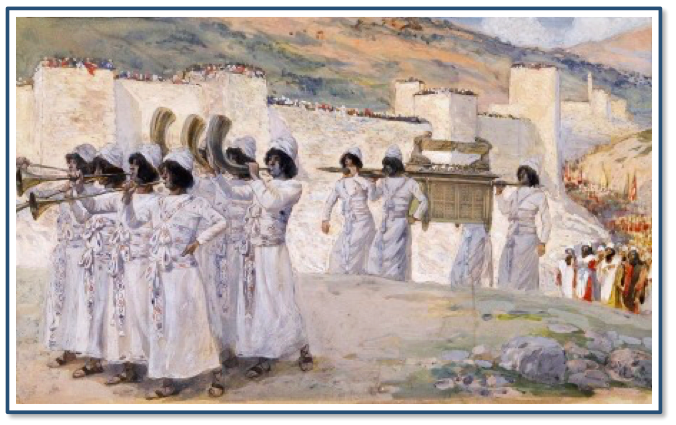

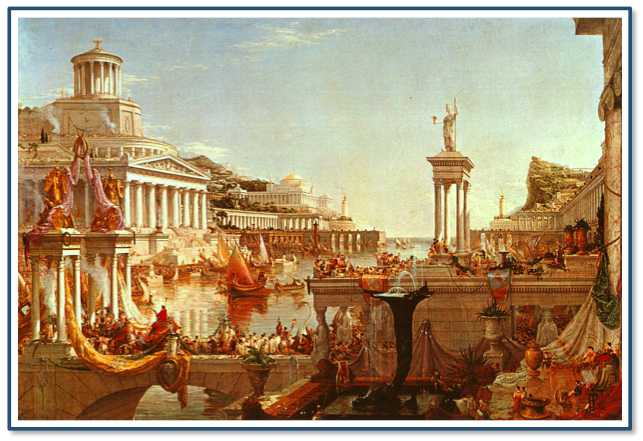

In the year 7,000 BCE, Jericho was the largest city on the planet—its population a whopping 2,000 souls.

Babylon, legend of exile and abandon, wouldn’t crack the top two hundred U.S. cities today. Its population was about 100,000—the same as South Bend, Indiana.

Ancient Rome at its height was as populous as modern day Dallas, Texas.

Yet somehow Jericho, Babylon and Rome are bigger than South Bend or Dallas. They have imaginative bigness. We see them: Israelites circle and trumpet. Hammurabi and Caesar Augustus stride in splendor. They swell, thrive, crumble and fall.

If the king’s pace was the measure of a yard, our dreaming marks the city.

Take New York. It hasn’t been the world’s largest city in decades. Yet it enjoys an imaginative station unattained by Jakarta, Manila and Seoul.

New York is a planet pulling in the best at everything—business, law, letters, the arts—in the relentless search for money, fame, accolades. For bigness.

The small are pulled toward the large. But unlike gravity, the pull of Gotham is psychic. Dreamers leave Muskogee and seek their measure in Manhattan.

The small make the big; the big defines the small.

//On Smallness_3//

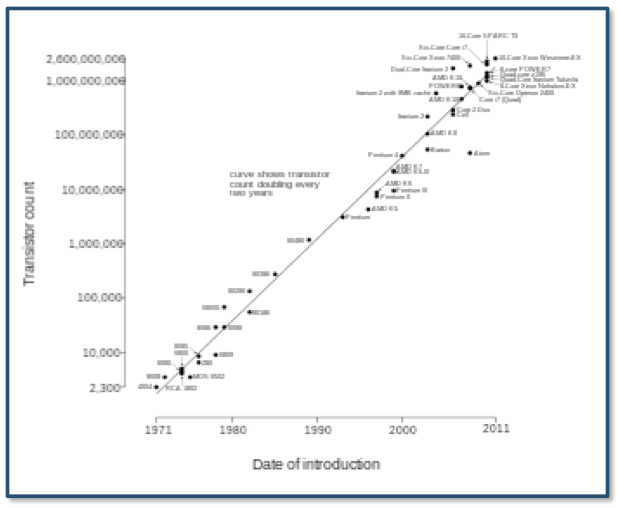

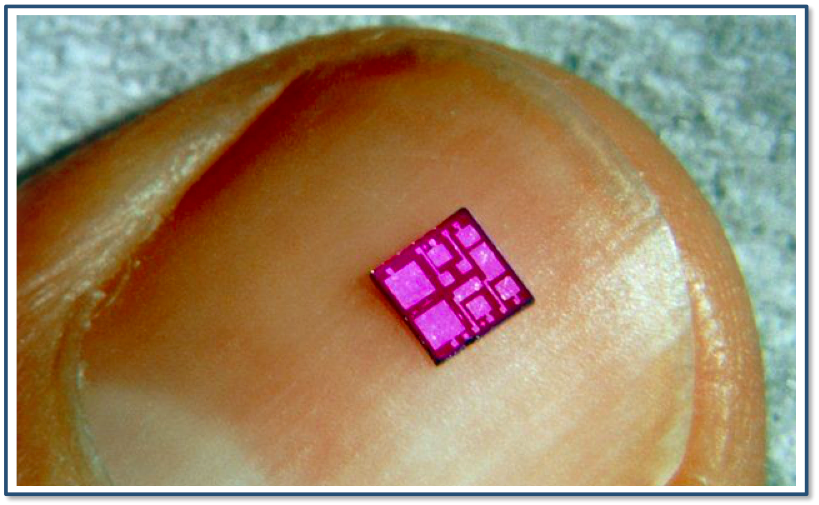

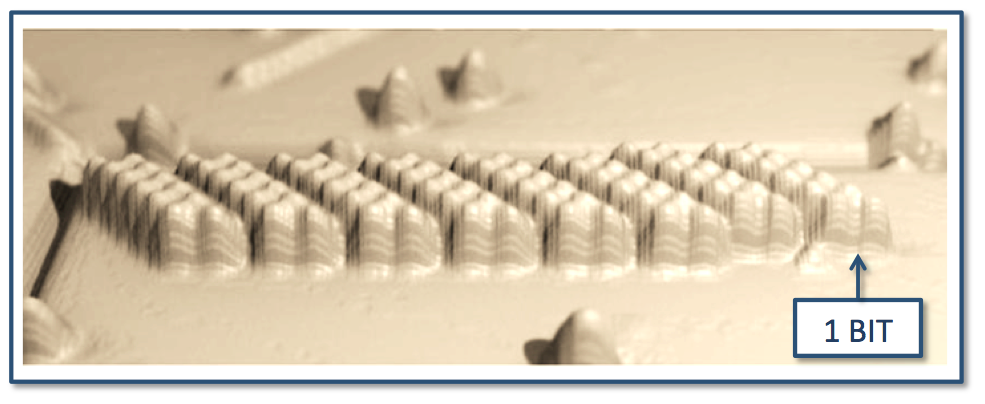

Moore’s Law—the principle of exponentially increasing processor speed—is a law of accretion. Progress is measured not in the smallness of the bit, but in the largeness of the processing power, the volume of computations per second.

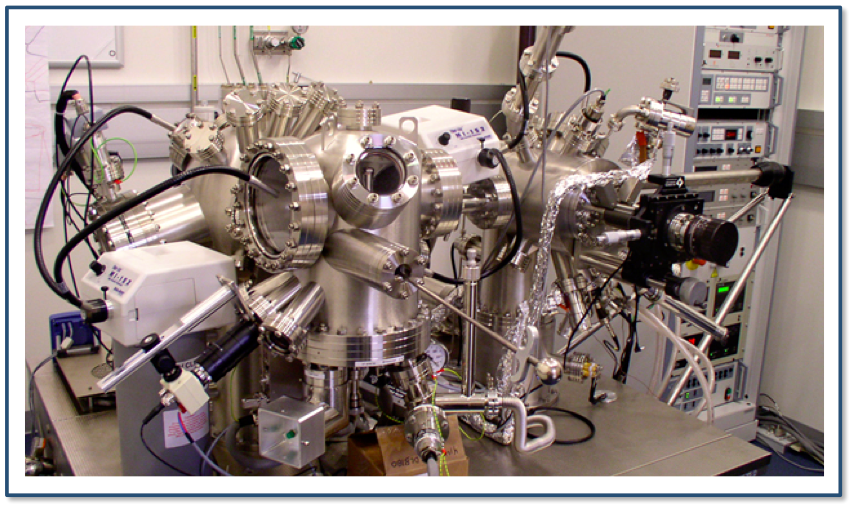

A single-atom bit would realize, perhaps, ultimate speed—and the end to Moore’s Law. To achieve such a feat of smallness, it will no doubt take a huge company like IBM, with a gigantic budget, big brains and steam-punkish rooms full of hardware like the scanning, tunneling microscope, below.

The quest for the atomic bit drives ambition and innovation. But we don’t seek the infinitesimal bit for its own sake. The smallness of it is only a means by which we achieve ultimate speed and power.

Computer engineering evokes an awe of the small made large. The drive of the discipline requires the packing of ever more information into smaller spaces. For decades we have marveled at its galloping feats of the miniscule.

The corollary to Moore’s Law is reduction, yet reduction chases the Law of More. Libraries disappear into thumb drives. More. We fight wars on a laptop. More. We slip the Internet into our pocket.

//On Smallness_2//

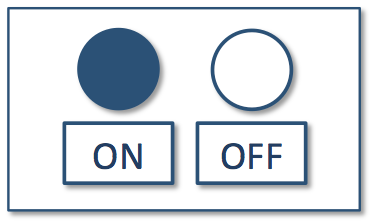

A bit is a single quantum of information. It denotes presence or absence. On or off. When we speak of the digital, we speak of a system in which everything is reducible to bits—to ones and zeros.

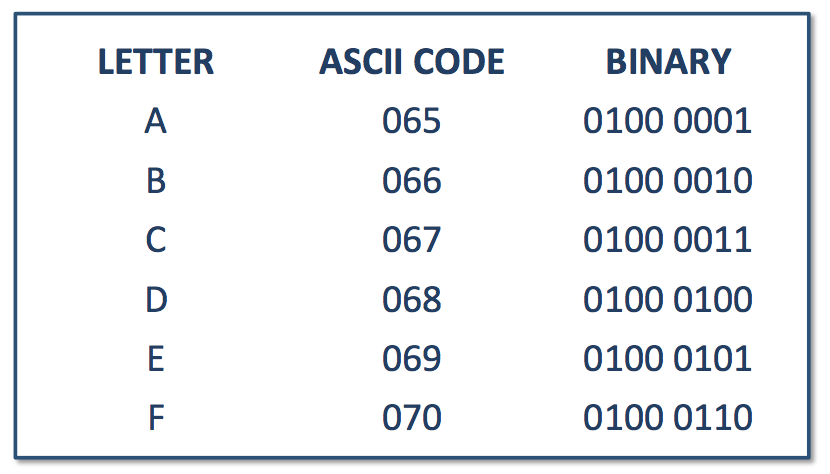

By convention, digital systems represent data in eight-bit sets, or bytes, each corresponding to a binary number. A binary number represents a value using only ones and zeros.

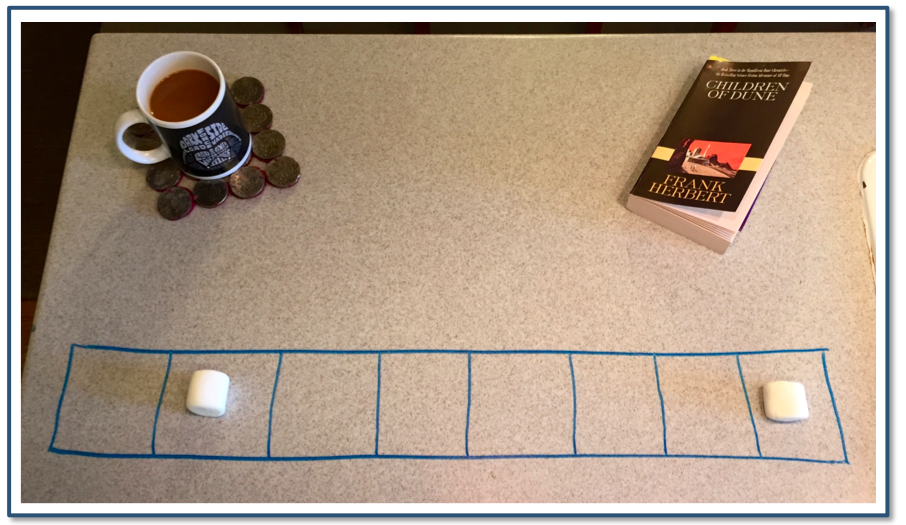

In the 8-bit system, an uppercase A corresponds to the binary number 65: 0100 0001. To demonstrate, below, I’ve represented an A using marshmallows. Essentially, I’ve stored an A on my kitchen counter.

A few years ago, IBM researchers were able to store a byte of information at a much smaller scale—using Iron atoms. Below is an actual image of the atoms produced by a scanning tunneling microscope.

Each set of twelve atoms represents a bit. The bits form a byte, enough to store a single letter. An A no bigger than few billionths of a meter long. At this scale, War and Peace written out in a single line would be about 1.7 cm in length, less than 5/8 of an inch.

An infinitesimal thread.

//On Smallness_1//

“I went to the Tim Hortons because I wanted to feel Canada, to be at one with its pulse and energy, to really get Canada down into my bones.”

– Olivia Townsend Ivagoe, travel writer

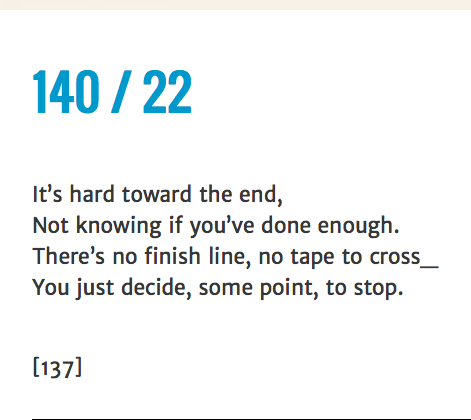

More than once, I’ve considered discontinuing the Instagram feed for this project.

The problem isn’t the photos, but these things:

The screen capture poems.

There is something off-key with the screen captures—something groping about them, something juvenile.

But then again, there is something groping and juvenile about this whole project, which adds to its perverse appeal. Too much is avoided when one fears being deemed a lightweight. And so I press on—even with the Instagram feed.

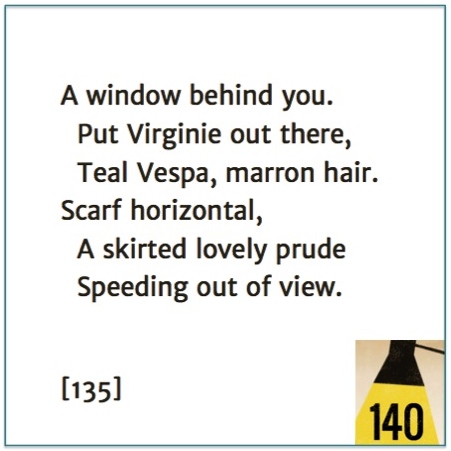

And still, something happens when one converts this:

A window behind you. Put Virginie out there. Teal Vespa, marron hair. Scarf horizontal, A skirted lovely prude Speeding out of view.

To this:

Some reduction occurs. The image changes the words, somehow cheapens them.

It may be the company that screen captures keep. This kind of cheerleading bollocks:

Or angsty scribbles:

Maybe.

Maybe it’s the lingering privilege we still give to books, which, at least inne ye olde dayes, were made by printing words on pages, not through the impregnation of a screen. Screen captures are doubly cheap: images of images.

But I don’t think it’s any of these.

I think it must be that taking photos of poems and posting them on the Internet is the final capitulation to the screen. A surrender to the mediocrity of the medium.

You look at these things and wonder whether it’s the end of the road for the poem, the poet or poetry—take your pick—and quickly thereafter follows the discomfort that comes from not knowing what to do with such morbid understanding.

But here_

Out here on the Interwebs you find the fret and the subduction of hope and malice, the tectonics of emotion. This is the place were the plates grind together uncomfortably. The process, the project, and the product may never be completely satisfying.

When I first started “writing for the web ecology,” I asked whether writing could survive on the Internet. The question presupposed a sort of battle between the weakling word on one side, and the brute image on the other. But the question—and the dichotomy—was misplaced.

Words and images aren’t enemies, as might be supposed. Rather, both are cohorts in whatever good or mischief they are put to. They can pull in the same direction to devastating effect (see, e.g., 1024/13).

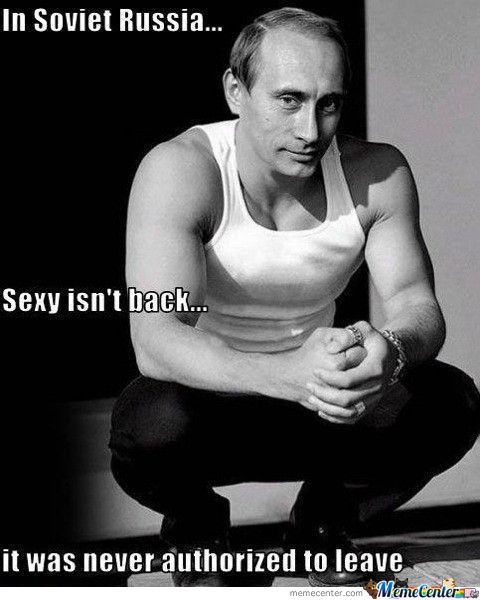

My kids are huge fans of the meme—those easy-to-chew visual candies that you can pop down on the bus or on the crapper. Most are stupid, some are brilliant. One of my favorites:

To be generous, you could say that the meme phenomenon is like an extended experiment in word-image orientation. They tell us a lot about how words and images work together.

Example 1:

a. The image arrests; it throws the punch:

b. Words change the image’s meaning; they redirect its force:

But it can work the other way around too.

Example 2:

a. Sometimes the image is dull and flat:

b. And words bring the party:

There’s just no easy way to disentangle word and image, except to admit that words require an interpretive skill—reading—whereas the image can simply be “seen.” But that doesn’t say everything. Reading images requires cultural knowledge. How else would this be so funny?

No, it doesn’t work to set the image up as the fall guy for the ills of the world, any more than does it work to complain about the inadequacies of words. Better to consider the uses they are put to, and complain (if it makes you feel better) about their content, about the cultural of distraction that has blossomed out of the fertile soil of the Internet.

My friend asked if I thought graffiti can be beaux art—high art. I know what the question means, but that doesn’t save it from being meaningless. Art is a name that we have given to a certain category of human endeavor that we imagine to be lifted up out of and somehow suspended above our daily experience. Art is important and timeless and ought to be preserved in marble buildings so that countless generations will henceforth be enlightened and elevated by it. And when I see Whistler’s Symphony in White, No.1 hanging majestically in the National Gallery, I am tempted to believe it.

But the terminology confuses. I wrote the sentence passively on purposes. The idea of art simply confuses. So if I am out riding a rented bike along the Donaukanal and I am arrested and moved and delighted and captivated and wowed and annoyed by what people have put there, by the excretions of their creative energies, exerted for whatever reason moved them, why should I have to worry myself about high art or low art or beaux art or any of it? I will take what they have done, and leave the word art to those who lack the confidence to simply feel their feelings.

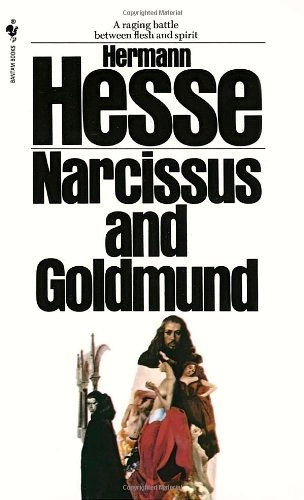

The Hesse poem was another in a series on the duality of flesh and intellect—It’s curious to me that when I wrote it, I was projecting eleven years ahead to 2015 and posing a question to which I can now blandly answer, “no.” I would have been surprised to say yes, and by now I think I’ve abandoned any thought of teleology. There is no end point, just wandering. Just look how Narcissus and Goldmund fell into my hands in the first place. I don’t know how I found the book twenty-some years ago. Was it in my parents’ books? In the library? And how did it get there? Well, Hesse had become hep in the American counter-culture 60’s, which launched an unexpected revival, putting Siddhartha and Steppenwolf on the shelves of teenage boys looking for paperbacks with naked babes on the cover (see Figure 1). These intellectual accidents worry me, and I have of late dumped solvents on my early ideas to see which will recongeal. Not that I have anything over Hermann—I’m not fighting the cleverness wars here—rather, all ideas want testing against the quiver of experience, most of all our best beloved.

I wrote 200/32 over ten years ago. What I meant then (and what I manage now) was the intractability that certain ideas have, and how, when adopted whole heartedly at a young age, never seem to go away, but rather go underground and ply their craft and make their mischief for years afterward. Back then, I was captured by the idea of the dichotomy of intellect and experience, the idea that life was either lived or thought about. The apotheosis was experience—not the natural inclination of a kid like me, who would rather hang back from all the fucking and fighting out there the big, big world. Nowadays, more often than not, I think that there is no line at all between thought and experience. My mind and ideas, such as they are, are implicated in everything I do. Ideas animate, not the least of which is the idea that animation is essential, the great Romantic bogey that chases people like me long after we have stopped believing in the essentialist myths of the likes of Alexis Zorba.

Breezewood, PA, November, 2014. The music is Appalachia Waltz by Mark O’Connor played backwards at about 1/2 time.

RECORD – FEDERAL SUPPLY SERVICE, STOCK NUMBER 7530-00-222-3525.

Between 11 and 31 January 2000, I kept careful track of all of my activities in a green government supply ledger. I filled five pages and gave up. Took longer to write my workday than to live it. Over the years, I’ve found dozens of these ledgers like mine, fragmentary records stuffed away forgotten in file drawers and credenzas. Each time, these abandoned ledgers bring to mind two contradictory thoughts. First is the sad continuity of things—how much the same our efforts appear beside those of who came before us. The second is the impossible uniqueness of life, how a million sentient moments pass per day unrecorded, how our attempts to record them are inevitably overwhelmed by the demands of the moments themselves. How the flow of life is incontrovertible. How despite even our best efforts to account for life, it almost entirely disappears.

On the walls of the Lakeshore Retirement Community hung drowsy pastel landscapes, soft focus details of Impressionist masterpieces—Manet, Monet, Renoir—the fin de siècle avant-garde rendered balm for fading vision.

In 1961, George Martinak deeded some 100 acres of forest, bank and marshland along the Choptank River to Maryland as a “natural area for the enjoyment of all.” Last weekend, I accompanied my son’s Boy Scout troop to the park to canoe and camp.

Around sunset, I slipped away from the troop and went down to the river to take pictures. Scrambling through brambles down to the bank, I found this field of water lilies stretching along the river’s edge.

My skills as a photographer are illusory; my Nikon D90 did most of the work. The serenity is illusory too. Out-of-frame, a red-necked ski boat whipped drunken circles. Hoots of laughter trilled above the drone.

Aldo Leopold wrote of preserving some tag-ends of wilderness, but always I find the tag-ends inadequate. They are mere comely fragments. And like photography in the digital age, they are cheapened by their sheer accessibility.

The park is insufficient, as are my skills, yet I find I must take part in these insufficiencies, if only to hold on to the tag-ends of their greater ambitions, and to draw out of them something resembling, more-or-less, the ends they fail to achieve.

Stars over Chéticamp Island, Nova Scotia. This photo was taken in August from the back deck of our rental house using my Nikon D90. I have a tripod but not the remote shutter release, so I had to stand and hold open the shutter with my finger, resulting in a bit of blurriness. I kept the shutter open for more than a minute, but the raw image was still too dark, so I further enhanced it on iPhoto, hence the reddish glow under the eaves of the house. The final effect is striking, but it is not what I saw when I looked up at the sky that night. The photo makes the sky seem closer, but that night the sky seemed to me bigger, farther away. I stood there, tired, trying to catch something of it. Yet, gone are the sharpness of the stars, the cold, brackish wind, the lapping of the water on the shore below me, the spooky, deep blackness of the ocean at night.

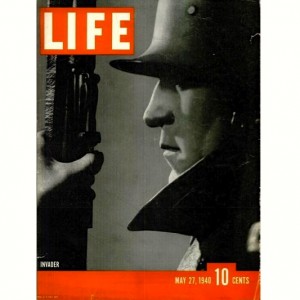

INVADER. May 27, 1940. The caption overlays the image like a transparency, putting a meaning on it. The INVADER is a German soldier; he stands for strength and aggression. The date is a caption; this is before Pearl Harbor, before intervention, the Final Solution, before Normandy, the Bulge, before Dresden, before surrender, division, the Cold War, and all that followed. 10 cents is a caption—an economy, now quaint, wherein a thin dime still had value. LIFE is a caption, recalling an era when the magazine still commanded attention. Lastly falls this caption, and suggests that all that came before was what it was, but was also, however faintly, about meaning.

The year before his death in 1949, Aldo Leopold published A Sand County Almanac, a book to be read as much for its prose as its philosophy. Leopold’s writing is surpassingly fluent, leathery, vivid. A favorite passage: “One swallow does not make a summer, but one skein of geese, cleaving the murk of a March thaw, is the spring.”

Leopold called for a “land ethic,” an evolution of ethics that balanced the interests of the biotic community with human desires. He understood that the cultural values that underpinned public and private action had to be reworked if there was to be any hope of slowing the decimation of America’s wilderness.

Leopold sought not only to shape ethics, but aesthetics. He recognized a paradox at the heart of conservation—that the more people are drawn to the wilderness, the more they tread upon it. He advocated uses of the land that would enhance its admiration while leaving sufficient wilderness for study and preservation.

Today, the successes of American environmentalism are uneven. The law remains obsessed with land as commodity, held in fee simple absolute. Yet Leopold still amazes, with the equipoise of prose and the depth of his thinking.

Ibn al-Haytam (Alhazem, b. 965, Basra) mathematician and optical theorist, argued that roughness produced beauty, and for that reason the goldsmith’s works became more lovely by having their surfaces roughened and textured.

Similarly, the interjection of a bad odor in perfume or a sour taste, however slight, in a dish, gives the perfume or the dish deliciousness. Why? Scents and tastes are inclined to go quickly from freshness to foulness. One could say that they are most delicious not at the height of freshness, but just after it, at the point of first descent.

Could it be that beauty is a matter of this subtle tipping from life into death? That what is beautiful for us is not the eternal, but the transitory? That all beauty contains that hint of death, that point of first descent?

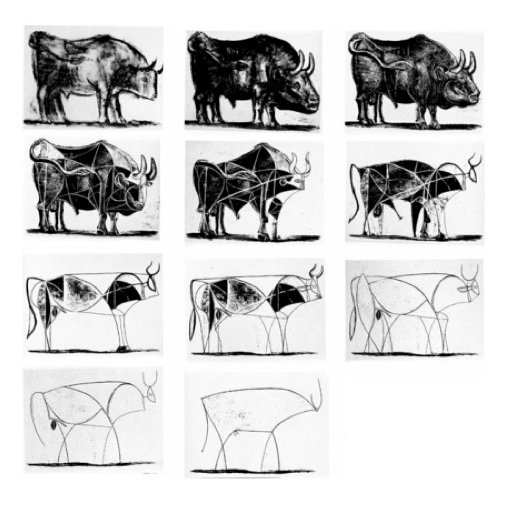

Eleven generations honed the bull to glyph. Picasso could have gone farther. The astrological sign Taurus is an arc surmounting a circle. But the end is not abstraction_it is the precise center point of simplicity and clarity. The picture word. Toro.

“There was something impenetrable about that year, something somnambulant—a winter’s afternoon watched out an upstairs window.”

– Janet Carson Clark, 1975

Plate 7. Vendramin Family, Titian (1543-7), National Gallery, London. An afternoon may be spent perusing from face to face, imagining the workings of this Venetian family. Perhaps most striking is how Titian depicts the boys. It is as if Mum dressed them up in their Sunday best but could not get them to sit still. One wonders if Andrea Vendramin (center, in red), having no doubt spent a considerable sum, was annoyed to find his sons looking this way and that. Or was he struck, as we are five centuries later, by the intense intimacy of their boredom? Titian’s genius is not in the faithfulness of their likeness but in the immediacy of their emotion. Fair warning for Mum (and Dad) who would cull the family album to empty smiles and wooden postures.

Figure 6. The ghost in the center is my mother. I am the toddler in her hands. One summer day forty years ago, enough sunlight was reflected from her skin, from her hair, from her clothes to ingrain this image on a strip of film. A billion other photons scattered, their collective moments indicating all directions. And because each traveled at the speed of light, each carried its own time with it. I wonder now. If I could find but one of those particles_if I could somehow get between it and the dark distance of all our endings_would there be enough light left to see what she was, or why, or what all this has meant.

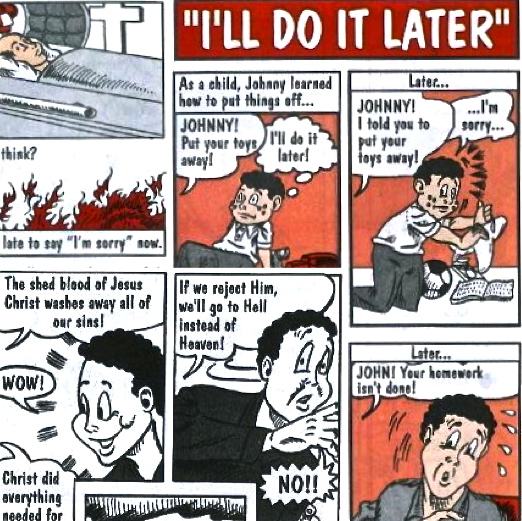

Someone keeps leaving these on the floor of the bathroom at work—a covert proselytizer scattering salvation around the toilets. In fourteen cartoon panels the pamphlet completes the following syllogism: You’ve put things off in the past. You’ve been punished for your procrastination. Don’t put this off: Call on Christ for salvation! It is a sermon as long as a bowel movement. And about as deep. But what a jarring interlude for the pooper—to rehash all the old guilt and arguments, to sigh or suffer, to say, “Yes but…” or shout out, “Damned right!” This phantom pamphleteer, whoever he is, has made a lyceum of our lavatory, a confessional of the toilet stalls.

Figure 4. Metaphor is the lead horse of literature, pulling ideas from one place to another. But it’s hard sometimes to tell head from hind. Case in point: Do these dinner rolls look like glowing briquettes, or do these briquettes look like dinner rolls? The answer is neither: These are baked marshmallows. Metaphor can lead_and it can lead astray.

The last of unspoiled arcadia is digital. I spawned into a jungle biome and spent the first night in a dirt hole while zombies groaned outside. Next morning, I built a better, wooden shelter. I mastered tools and spent nights mining rather than crouching in fear.

Soon, I struck off and found a spot between the forest and plains, not far from the seaside. I built a large stone house, smelted iron, and made armor. I lured in cows and chickens, planted rows of wheat. I tamed a horse and rode out on patrols.

One night, I lost my horse in a storm. Running hard for home, low on food, and chased by creepers and skeletons, I came over a rise and saw, all at once, the blaze of my complex, and felt a deep and ancient satisfaction. I ran through my gates, climbed the leveled hills, and ducked into my redoubt. I ate cooked meat and slept a blank, dark sleep until sunlight blued the distant hills.

That evening, I climbed a bluff overlooking the sea and pictured a new and better complex—with a glass castle, fake beach, boat launch, and diving tower. A Minecraft Club Med.

Some places live up to their clichés. In the west of Ireland, we saw more rainbows in one week than we had in the preceding ten years back in the States. They came down in abundance_singles, doubles, some far off, some right outside the window of the car. We even saw some touch down in the foreground, in front of the horizon line, just right there_and you can imagine the ensuing scramble for leprechauns and pots of gold. But, alas, our rainbows only found power lines and penny walls.

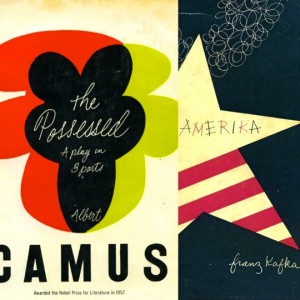

The lamp motif of this website, designed by my friend Melissa Armstrong, was inspired by mid-century Modernism. In the 1940’s and 50’s designers like Alvin Lustig and Paul Rand created book jackets for works by authors ranging from Henry Miller to Gertrude Stein. The designs were simple and bold, ideal for paperbacks and reprints. These were books to be dog-eared—to be passed around, beat up, contended with. Passages were underlined. They fell out of bed. Today, they are found at bookstalls and garage sales, musty pages recalling a thirst for obscurity and a thrill of the illicit that has lost its potency. Like all things past, we cannot recreate the time or place, but only pay them homage—a nod (or a bow) to three colors and a silkscreen.